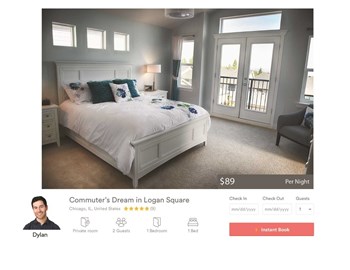

The media and political buzz surrounding so-called 'homeshare' or 'short-term rental' websites (primarily Airbnb, but also other similar services like Homeaway.com and VRBO.com, just to name two) has been on the upswing over the last year or so. It sounds like a perfect arrangement; You go on vacation, and rent out your home while you’re gone—you get a house sitter who pays real money, instead of the other way around.

Or, you stay home, and rent out your spare room—making a few hundred (or even a few thousand) dollars without doing anything more than washing your extra set of sheets and wiping down the counters. It’s all part of a growing trend called homesharing, which is taking so-called 'destination cities'—and the areas surrounding them—by storm.

An Ideal Idea?

Homesharing is especially popular—and controversial—in cities and surrounding suburbs where rents are ridiculously high (hello, New York!), and residents are taking advantage of how much people are willing to spend by renting out their own places whenever they can. Right across the Hudson from Midtown Manhattan, within sight of hotel rooms that start at around $250 a night, visitors can rent a 'gorgeous and cozy' bedroom in Jersey City for $85 per night, or a 'luxury room minutes from Manhattan' for just $40 per night. In Hoboken, you can rent an entire townhouse just '15 minutes to New York' for a mere $149 per night. Indeed, for renters and for those doing the renting, when it comes to homesharing, the sky's the limit in terms of what you can get for your money, and how much cash you can make.

But while thousands of apartment owners in cities like New York, Chicago, Boston and San Francisco love being able to monetize their units by renting an extra bedroom (or even their whole place, if they're out of town) to a visitor or tourist, condo association and HOA boards and management are typically less enthused about the trend. A constant stream of non-resident visitors raises security concerns, adds wear-and-tear to common areas, and complicates the enforcement of house rules. Depending on the city, short-term rentals may also run afoul of zoning and hospitality laws.

Homeshare History...and the Law

The biggest player currently in the homesharing game is without question San Francisco-based Airbnb Inc. Founded in 2008, the service allows anyone to list their house, condo association, spare room, couch, boat, treehouse or any other living area for short-term rental. More than 9 million people in 34,000 cities have checked out Airbnb—with more than 500,000 listings across the world—so this trend is certainly not shrinking or going away.

In fact, according to the company, on December 31st of 2014, Airbnb had its biggest night in history of the company, with nearly 550,000 travelers using the company to stay in more than 190 countries. Of those, 91,000 were guests using Airbnb for the first time, and 22,000 hosts were new, too. That’s compared with five years ago, when only 2,000 people used Airbnb on New Year’s Eve.

While the homesharing trend is no doubt massive, in many instances it runs afoul of community governing documents, which typically forbid subletting an apartment for anything under 30 days, says Paul Santoriello, PCAM, CMCA, AMS, president of Taylor Management Co., based in Whippany. “Every governing document is different, but in general, management is looking for leases greater than six months. Usually, they're looking for a year or more."

That caveat stems from the practice of some unit owners of buying multiple properties, setting them up with furniture, hiring a maid service and renting them out to executives or other individuals for short-term stays, adds Gary Wilkin, owner and president of Mahwah-based Wilkin Management Group. That practice, while not so common in the post-recession economy, causes hardship for the community association, creating a transient population in areas that are looking for long-term stability.

Across the river in New York City— where in addition to condo association documents, state law also prevents subletting for less than 30 days—the penalties for homesharing 'hosts' who get caught can be severe, says Adam Leitman Bailey, real estate attorney and founder of Adam Leitman Bailey, PC, based in Manhattan. Bailey has been involved with more than 100 cases concerning homesharing within the past year, and says hosts who rent out their apartments to short-stay visitors can incur penalties of up to $1,000 per day. Because it’s so difficult to do this legally, chances are that most people who host are in violation.

“Even if they have a lease for more than 30 days, they need commercial insurance, which is very expensive, and many insurance companies won’t give you commercial insurance,” he says. “You may be violating your lease by using your unit as a business because almost all associations ban subletting.”

Popular...But Not Really OK

The popularity of homesharing is matched only by backlash against it. Last year, illegal hotel complaints―like Airbnb and other short-term rental places—increased 62 percent.

Still, it’s all about the money, and Airbnb is big business.

While it doesn’t look like they’ll stop any time soon, the government is catching on. Up until February 15th of this year, Airbnb was blamed for not collecting hotel taxes from many of its hosts—and for essentially allowing its members to use their apartments as ad hoc hotels, taking away business from real, legal hotel businesses. Last year, Airbnb began collecting taxes in San Francisco, Portland and some other municipalities in California, and they’re extending the practice to more cities, including Chicago and Washington.

In January of this year, a New York City housing court judge evicted a rent-stabilized tenant for using Airbnb to profit off of his rental while he and his family were living elsewhere. It is the first recorded case of someone being evicted for using the service.

Legal or not, lots of people are using Airbnb and similar vacation rental services, regardless of whether or not they own their own building, own their own unit or just rent.

Most are doing it because this is such a lucrative and seemingly easy way of making money. Still, the pros spoken to for this article agree that before anyone even thinks about homesharing, they need to see what the bylaws of their condo association or HOA say. Also, says one attorney, “If you’re still going to go ahead with this—you should do some things to make it safer.”

Some attorneys, for example, recommend starting by taking photos ahead of time to show the condition of the condo association, so if any damage is done, you have grounds to prove that it was done by the person renting the apartment. You should also do a walk-through with the renter and an inspection, and get a legal agreement to require the tenant to return the home in the shape that it’s given in. There should also be a small security deposit.

Nevertheless, one condo association board member says that people are still probably taking those risks. His building does permit 30-day leases, but doesn’t allow anything shorter than that. However, he says that short of checking everyone who enters the building, it’s difficult to discern whether someone is using Airbnb. “No one would advertise it, so you would never know,” he says. “It probably has happened here, but who knows?”

If You Insist…

Bailey says that there are a few ways to stop homesharing in your building community if you don’t want it to occur. If you see people constantly coming in and out of a given apartment with suitcases, then that’s a sure sign that the owner or legal tenant is renting via a homesharing company.

“If you’re on a board and want to stop Airbnb, you should stop people from going upstairs,” Bailey continues. “Don’t let strangers go into the building unless the owner is there.” Bailey does admit that “If they say they’re a cousin or an uncle, however, it gets fuzzier.”

Undesirable as homesharing may be for a board or manager, the reasons why owners participate in it can be just as serious. Perhaps the person doing the renting is desperate because they’ve lost their job, or just had some other huge or unexpected expense. “They’re unable to pay their bills, and homesharing allows them to pay their mortgage,” Bailey says.

In an expensive part of the country, that’s very compelling but the last reason to forbid homesharing in an association or a condo association, and to eschew the practice as an owner, is that on top of the possible $1,000-a-day fine, the person renting out their apartment can get evicted and foreclosed because they could be violating terms of their lease, Bailey says. “I have tons of cases like this,” he says. “It’s huge.”

And it’s not going away anytime soon.

Danielle Braff is a Chicago-based freelance writer and a frequent contributor to The New Jersey Cooperator.

Leave a Comment